“We found that in brain,age-related changes very often have to do with the loss of molecules that help signals to spread among neurons. This could explain why old rats have a reduced ability to form new connections between neurons, as well as other traits observed in the aging brain,” says Martin Beck, who led the work at EMBL. “And it is very similar to what has been found in previous studies that have looked at gene expression in humans.”

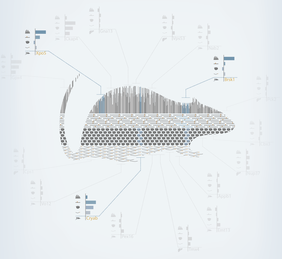

The scientists compared brain and liver cells of rats in the prime of life – 6 months old, roughly equivalent to 18 year-old humans – to those of old rats – 24 months old. Rather than focus solely on gene expression – which genes are turned on or off – as most previous studies had done, the team employed a variety of techniques to assess several steps in the cells’ protein production assembly line. They measured which parts of the genome had been transcribed into RNA, what proteins the cells had produced, what rates proteins were being produced at, and what chemical markers were added to proteins in ‘post-production’.

“Integrating data from different levels was crucial,” says Beck. “When you see how the data sets cluster, it reveals what’s actually going on. Often it was only then that we could see that a whole network of reactions is affected.”

Ageing impacted some networks equally in liver and brain – notably immune response and inflammation, and stress responses – implying that these are probably general effects of ageing, felt throughout the body. But other effects were very specific. The livers of old rats showed changes in metabolic processes – i.e. how cells process molecules – mostly at the level of regulating how the genome is ‘read’. In the brain, by contrast, the tell-tale signs of ageing were mostly at the level of protein production, and mainly affected signalling processes that enable neurons to communicate with each other.

“We chose to compare brain and liver because these two organs have very different capacities for self-renewal,” says Martin Hetzer, who led the work at the Salk Institute. “The liver has a very high regeneration rate, so even in an old animal – or person – most of the molecules in liver cells will actually be relatively young. In the brain, it’s the opposite: in our previous work we have shown that many sets of molecules in the brain are effectively there for life.”

“This is just the beginning,” says Nicholas Ingolia, who led the work at Berkeley. “Our study provides a rather large resource of proteins, RNAs and post-translational modifications that are affected by age, which we hope others can use to propose new hypotheses which can be tested experimentally.”

Source article

Ori, A., Toyama, B.H., et al. Integrated genome and proteome-wide analysis reveals organ-specific proteome deterioration during aging in rat. Cell Systems, 17 September 2015.